Should Malta be moving away from the manufacturing industry?

Nominal labour productivity per person employed (ESA 2010) - Where does Malta stand?

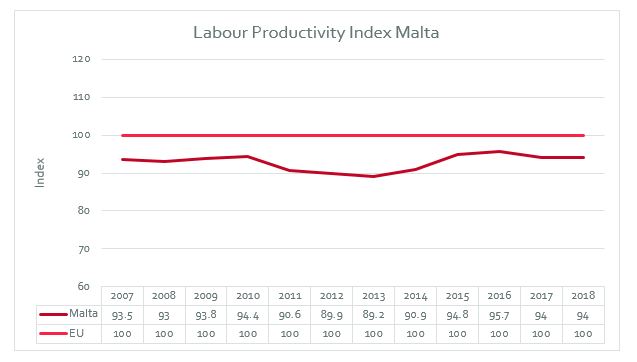

On 20th January 2020 Eurostat published indicators on productivity for the period between 2008 and 2018. The indicator is derived by dividing Gross domestic product (GDP) for the period by the number of individuals employed for the corresponding period.

GDP per person employed is intended to give an overall impression of the productivity of national economies expressed in relation to the European Union (EU28) average (EU28 = 100). If the index of a country is higher than 100, this country's level of GDP per person employed is higher than the EU average and vice versa.

The Graph below shows the labour productivity index (LPI) of Malta between 2007 and 2018. Over the past years Malta’s GDP growth has outperformed many European countries, however, one of the main drivers of this growth was the increase in population and number of people employed. The graph below shows that the labour productivity index of Malta has remained constant between 2007 (LPI = 93.5) and 2018 (LPI = 94). This indicates that although Malta’s GDP has gone up, its labour productivity, compared to the EU average has remained the same, at just below the EU average.

In contrast to Malta’s constant LPI, other countries have managed to increase their LPI. The country that managed to increase its LPI the most was Romania which registered a 25.1-point increase (57.4%) from 43.7 in 2007 to 68.8 in 2018. Ireland registered the second highest increase in LPI with an increase of 54.6 points (39.2%) from 139.2 in 2007 to 193.8 in 2018. Other countries that registered a significant increase in LPI were; Latvia 26.3% (+14.3 points), Bulgaria 25.5% (+9.6 points), Poland 25.3% (+15.5 points) and Lithuania 22.5% (+13.9 points).

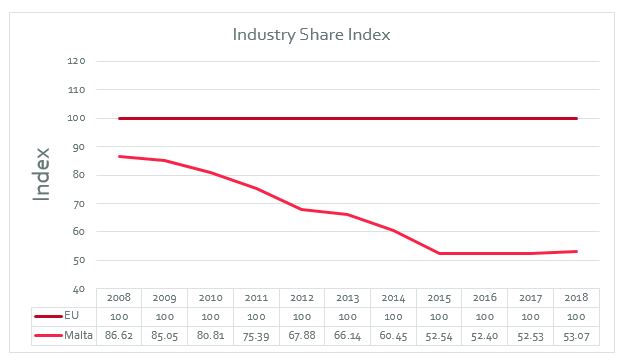

An analysis of these countries reveals that they have either increased their share of Gross Value Added (GVA) coming from Manufacturing, mining and quarrying or other Industry OR actually a large share of Gross Value Added (GVA) is derived from Manufacturing, mining and quarrying and other industry. If one had to index the share GVA of these sectors as a percentage of the total GVA and expresses them in relation to the European Union (EU28) average (EU28 = 100) this observation becomes more evident. This index is as follows; GVA share from these sectors as a percentage of total GVA and will be referred to as Industry Share Index (ISI).

Romania has averaged the fourth highest ISI between 2007 and 2018 with an average index of 151 meaning that during these years, Romania’s share of GVA derived from Manufacturing, mining and quarrying and other industry was 51% higher than the EU average.

Ireland has averaged the third highest ISI between 2007 and 2018 with an average index of 152. Ireland has also registered the largest increase in ISI during the same period from 113 in 2007 to 191 in 2018 (+78 point = 68.8%)

In contrast, Malta has averaged the third lowest ISI and the largest decrease out of all countries between 2007 and 2018. In 2007, Malta’s ISI stood at 87 meaning that Malta’s share of GVA derived from manufacturing, mining and quarrying and other industry was only 13% lower than the EU’s average. However, in 2018 Malta’s ISI has decreased by 34 points (-38.7%) to 53 points, half the EU’s average.

Hence, as Malta decreased its share of GVA derived from the manufacturing industry it has failed to increase its productivity. This begs the question, should Malta be moving away from the manufacturing industry and if not, what kind of manufacturing industry should it try to attract?

Has inequality in Malta increased?

Third Wave of the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS)

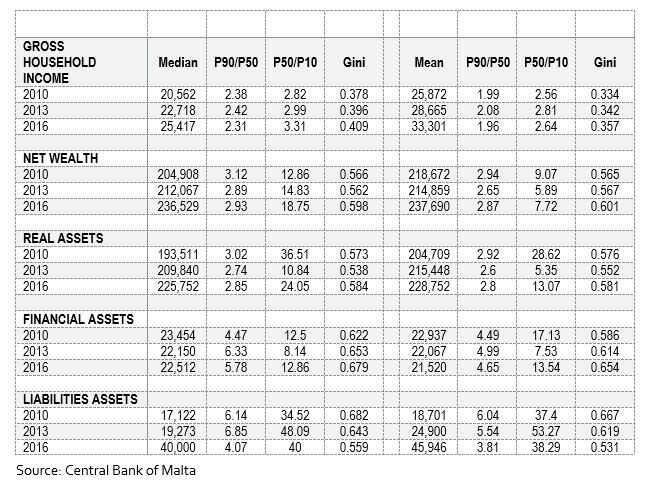

Recently the Central Bank of Malta published the results from the Third Wave of the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS). The HFCS contains a wealth of information on households’ balance sheet, income and consumption patterns.

Table 1 reports some widely used measures of inequality for gross household income, net wealth, real assets, financial assets and liabilities, for the whole sample of participating households and households with a reference person of working age. The full sample results show that, according to the Gini coefficient, financial assets are the most unequally distributed variable among the ones chosen. Furthermore, their distribution on this basis has become more unequal over time.

The Gini coefficient measures the inequality among values of a frequency distribution (for example, levels of income). A Gini coefficient of zero expresses perfect equality, where all values are the same (for example, where everyone has the same income). A Gini coefficient of one (or 100%) expresses maximal inequality among values (e.g., for a large number of people, where only one person has all the income, and all others have none, the Gini coefficient will be very nearly one).

The distribution of gross household income is less concentrated than that of net wealth, as evidenced by the lower values of the Gini coefficient and P-ratios. Furthermore, while the P50-P10 ratio – that is, the ratio between the 50th percentile (median) and the 10th percentile, which covers the bottom half of the distribution – indicates rising inequality across the three waves, the P90-P10 ratio suggests decreasing inequality in the upper half of the distribution.

In 2016, households at the top of the income distribution earned 2.31 times more than those at the median of the distribution, down from 2.38 in 2010. Concurrently, households in the middle-to-upper parts of the distributions saw higher income increases relative to lower income groups. This has resulted in a small increase in the Gini coefficient over the period under review.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore updated its regulations for digital payments

The Monetary Authority of Singapore updated its regulations for digital payments

With effect from 28 January 2020, The Monetary Authority of Singapore (“MAS”) requires all crypto businesses operating in the country to seek licensing. The companies will be asked first to be registered and then apply for the licenses. The existing crypto firms will have one month (starting from the 28th of January) to register at the MAS and then they will be granted a 6 months period during which they shall apply for their payment institution license.

This requirement stems from the Payment Services Act (“PSA”) which was passed in January 2019. The article 2 of the PSA explains what “Digital payment token” is and this covers all crypto related firms and crypto exchanges. In particular, the article 6(2) of the PSA defines three types of licenses:

- a money changing licence;

- a standard payment institution licence;

- a major payment institution licence.

And each service provider may hold only one of the abovementioned licenses. This also means that such companies must comply with the with anti-money laundering (“AML”) and counter financing of terrorism (“CFT”) requirements.

By doing so the MAS seeks to strengthen consumer protection and promote the use of electronic payments. Given the fact that all EU member states have to comply with the provisions of newly introduced 5th AML Directive, Singapore tries to win a share of the market and lure some of the businesses. For instance, one of the most known crypto exchanges – Binance has announced that via their office in Singapore they have applied for the licensing. It shall be noted, that Binance was one of the first ones to move some of its operations to Malta and apply for the Maltese VFA license.